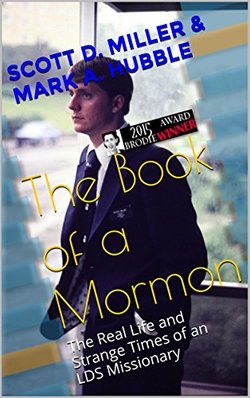

A few months ago, I learned that Dr. Scott Miller (one of my favorite clinical writers and thinkers) wrote a memoir about his 2-year experience on a Mormon mission. In the next breath, I jumped on Amazon to order my copy. I initially encountered Scott Miller and his associates’ work in 2009. Around this time, my frustrations with the dogmatic nature of the leadership surrounding my primary therapeutic modality of practice, EMDR therapy, mounted to the point that I almost abandoned it as an intervention. Then, I heard Dr. Scott Miller speak at a conference and I found his whole view of our psychotherapeutic professions to be refreshing. His willingness, like Dr. Saul Roszenweig before him, to make comparisons between religious devotion to a certain faith denomination and zealous devotion to a school of psychotherapy impressed me. Almost immediately into reading The Book of a Mormon, my understanding for why I admire Scott Miller so much deepened. I was impressed, in the first pages, at the way his tone did not come across as anti-faith. Indeed, in speaking of those who engage in practices like going on missions as an expression of faith (or doing what they believe to be the right thing), Miller writes, “No one who goes through such an experience merits scorn or ridicule, much less disinterest. They deserve our empathy. This is what I hope to achieve by revealing the real life and strange times of my own mission experience.” As someone who worked for a pretty conservative parish within the Catholic church for 2 ½ years following my undergraduate education, I was asked to do things I didn’t really believe at my core. However, the church had me believing that their way was the right way. As a girl who wanted so desperately to do the right thing, I followed suit. I felt Miller’s extension of empathy envelope me; I can still struggle with feelings of shame and regret around actions I performed in the name of God/the church while working on my own version of a mission. Miller’s tales that compose the book are whimsical, insightful, and dripping with humanity. The cast of characters that he introduces (particularly the rigid mission area president) and his series of mission companions that he served with during his two years in Sweden, particularly animate these stories. His interactions with locals within the Sweden-Goteborg mission area were especially well told and full of spirit. These individuals struck me as his real teachers during his two-year mission. I was particularly moved by Miller’s account of meeting a non-Mormon Swedish woman, the first person he ever met to have a sambo (living companion). Miller’s reflection upon how she seemed to be a happy, well-adjusted person without any kind of faith and while living in a manner that flew in the face of everything he’d been raised with as a Mormon was particularly moving. Another highlight of his memoir was witnessing how he connected the dots about the way that the Mormon script for evangelizing completely contradicted Swedish cultural norms. Miller’s challenges to these aptly observed contradictions were swiftly shut down. Not only did I relate to many of these tales, I found them to be the pivotal observations that would go on to inform my career as a helping professional. I found myself wondering if Miller views his own challenging of the rules in a similar way. In the end, Miller survived his two-year mission and emerged from the experience with a strong competency in the Swedish language (enough to earn a minor in it from Brigham Young University, where he completed undergrad) and a refreshed perspective on how the world works. It was a perspective that seemed to grow from many early days of wondering if he could get through this experience, to being able to mentor others on mission with him, particularly with language skills, and to become able to practice empathy where so many others could not. Miller reflects, “The experience irrevocably changed me. Everything I grew up believing about what most matters in life—family, faith, friendship—was turned upside down. Actually, it was ripped away. I was no longer innocent.” I am grateful that Dr. Miller chose to put himself out there in this fashion and share about this time in his life in such an honest, candid way. As he noted, his tale is not one of scandal and salaciousness that we sometimes crave when we pick up church memoirs of this nature. His tale is of a young Mormon kid whose world was rocked by serving in this capacity. Indeed, reading the stories that comprised this rocking and its resulting awakening can be a learning experience for others who are in some way finding their entire worldview challenged. I believe that many more of us who work in psychology or the helping professions have stories like this to share—of losing faith and finding it all over again when we start to challenge what we’ve been told to believe… of learning to have faith in ourselves and what we are observing about how the world works.

1 Comment

|

Dr. Jamie MarichCurator of the Dancing Mindfulness expressive arts blog: a celebration of mindfully-inspired, multi-modal creativity Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

|

Contact |

Memberships & Affiliations |

|

Please direct all inquiries to:

[email protected] © Mindful Ohio & The Institute for Creative Mindfulness, 2021 Terms of Use Privacy Policy |

Dancing Mindfulness/The Institute for Creative Mindfulness is an organizational member of the International Association of Expressive Arts Therapists, the Dance First Association, and NALGAP: The Association of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, Addiction Professionals and Their Allies; Dancing Mindfulness proudly partners with The Breathe Network and Y12SR: The Yoga of 12-Step Recovery in our shared missions.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed